Adapt to Preserve is a proposal for the city of Cape Charles, Virginia, that offers a new strategy for the treatment of historic landscapes, one of “adaptation”: enhancing existing design features to adapt to changing environmental pressures while offering new features to preserve the memory of spaces inevitably lost. Cape Charles’s historic urban grid, the first of its kind in Virginia, will be inundated and erased by the rising waters of the Chesapeake Bay. Beginning from studies of the city’s urban form and features, this adaptive strategy proposes that a portion of the historic grid be reverted to a historical dune landscape that can shift and grow to protect the city from higher tides. New circulation paths giving recreational access to the dunes are placed along the position of the lost grid to preserve its memory. The project protects the city from inundation while also preserving its cultural and ecological character and in turn its economic position as a destination for tourists and locals alike.

Diagram of the downtown historic district

2070 sea level rise predictions superimposed onto a historical map of Cape Charles (1887). The white line represents the 2019 mean high tide line. (Basemap: New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Existing zoning superimposed onto a historical map of Cape Charles (1887). The present development of the city very closely follows the original plan of the town, with much of the previous estate of William Lawrence Scott now the special Planned Unit Development. (Basemap: New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Tazewell Avenue 1910 / 2019 (Cape Charles Historical Society)

Randolph Avenue at Peach Street 1910 / 2014 (Cape Charles Historical Society / Google Street View)

Cape Charles Harbor 1925 / 2018 (Cape Charles Historical Society / Aerial Photograph © At Altitude Gallery)

Photocollage of the city's sole dune

Selections from a catalog of fence types found throughout the city

yet fragile landscape will be offered by storm-resilient boardwalks modelled after dune fencing. Six boardwalk paths will travel across the dunes and align with the existing urban grid. An alternate, interdunal path will wind its way north to south, passing underneath the orthogonal paths and connecting the park to the historic railyards and marina.

Site plan of the design proposal with a new dune park occupying the space of the Sea Cottage addition

Early concept image exploring the scale of the new dune system in relationship to the existing shape of the city

Existing undeveloped parcels (as of 2019)

Potential infill relocation of historic structures in the Sea Cottage addition to vacant parcels

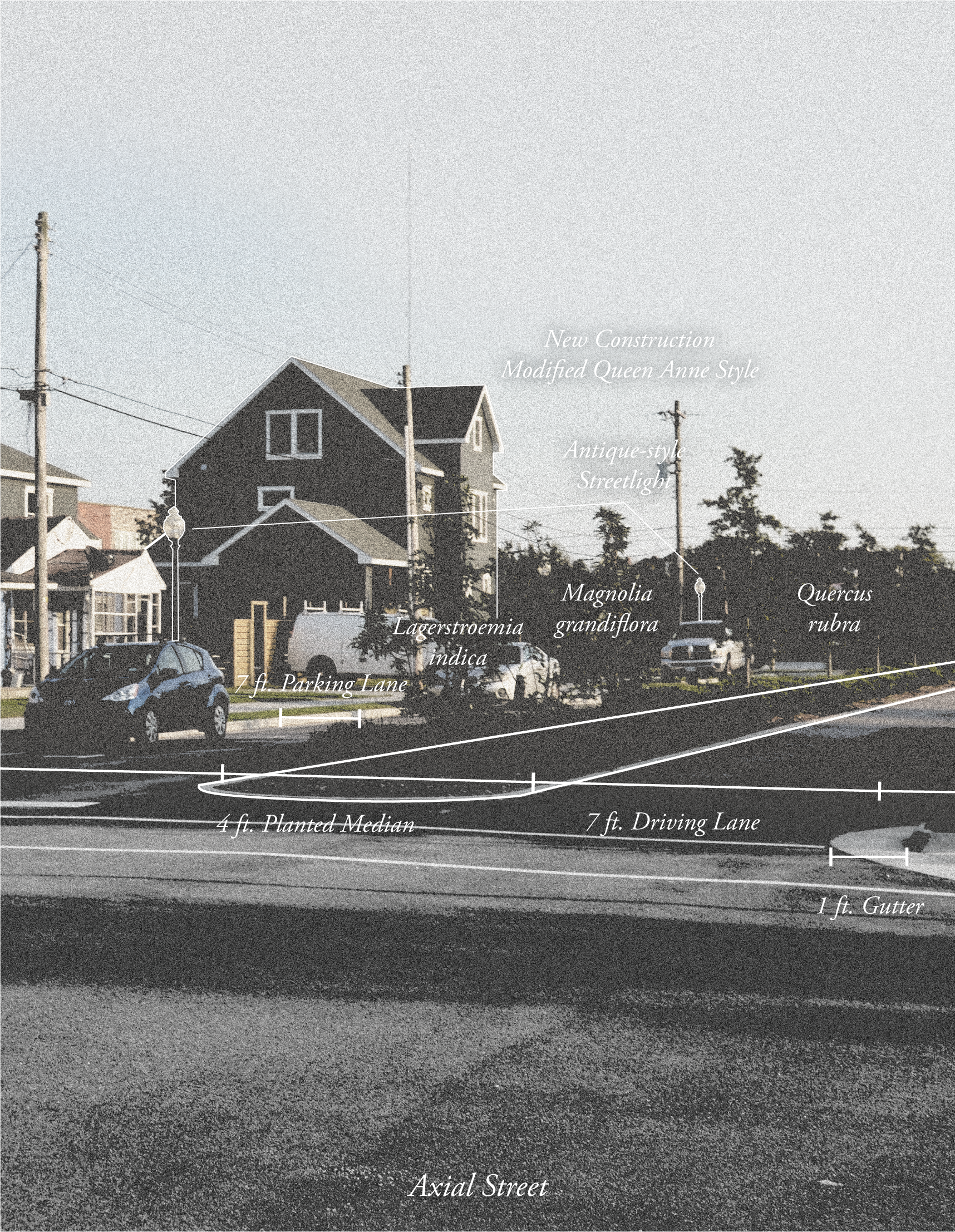

Detail plan with planting of the central axis

Section of the central piered path boardwalk with a gradual incline bringing visitors from the street up and over the dunes to bay views

View from the north-south boardwalk within the dune park